This article was previously published in the October 2018 issue of hfm. Copyright 2018 Healthcare Financial Management Association.

Hospitals across the country have seen many changes in the past seven years as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has evolved and states have implemented optional components of the legislation.

Hospitals across the country have seen many changes in the past seven years as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has evolved and states have implemented optional components of the legislation.

The constant threat of repeal and replace as well as the new tax-reform legislation have created certain unknowns for hospitals. Chief amongst these are reimbursement from government payers and the effect of the overall insured rate, which have kept providers on the edge of their seats.

Background

Under the ACA, many states expanded Medicaid coverage, attempted to roll out exchanges for commercial plans, or both. These changes have required the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to begin modifying certain payment methods to hospitals to redirect funds from their prospective payment systems to pay for the expansion of coverage in other areas of federal and state spending.

Coverage through exchanges and changes to employer-based health plans had the intended effect of providing or modifying coverage for many individuals, changing the category of these patients from uninsured to insured. Unfortunately, while this was occurring, many exchanges and insurance co-ops failed.

Although now technically insured, a large number of these individuals have high-deductible health plans (HDHPs), which have deductibles that often exceed $5,000. This high deductible level essentially places individuals who have difficulty meeting their patient financial responsibility—and who consequently may qualify for financial assistance to meet these obligations—in the self-pay or charity-care category.

One of the biggest challenges with the influx of insured individuals who still qualify for charity care is the process by which CMS determines hospital reimbursement payments.

Changing Landscape

In the current environment, extraordinary financial pressure is looming over the health-care delivery system. This may result in a renewed spike in uninsured and underinsured populations, continuing uncompensated care issues across the country. There are three primary causes driving this trend.

Individual-Mandate Penalty

The recently enacted tax-reform law, commonly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), eliminated the individual mandate penalty beginning in 2019—a move which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates will result in the following changes:

- Thirteen-million additional uninsured individuals by 2027

- Average health insurance premium increases of around 10% per year over the next decade

More conservative estimates still show significant increases in both those who choose not to be insured when there are no penalties as well as those who are priced out of the escalating insurance markets.

Growing US Debt

Tax reform is projected to incur just short of $1.5 trillion in new debt over the next 10 years. At that time, the CBO has estimated publicly held US debt will approach 100% of the country’s annual gross domestic product—a key ratio many experts believe will put considerable strain on the economy as interest rates rise and available credit is reduced.

As political leaders grapple with this issue, they’ll need to address the largest budget-line item: federally provided or subsidized health insurance. This area includes the following:

- Medicare

- Medicaid

- CHIPS

- Market-exchange subsidies under the ACA

Efforts to rein in spending from these programs will likely either reduce the number of individuals insured or reduce the benefits available to enrollees.

Medicaid Expansion

The ACA incentivized states to expand their Medicaid programs by covering 100% of the expansion costs for a period of time. That level of federal funding is scheduled to be reduced, and states are struggling to identify how they’ll pay for the shortfall.

This reduction will put pressure on the 32 states that expanded to either reduce benefits or cut back on enrollees in their Medicaid programs. Ongoing health-care reform attempts and annual congressional budget discussions continue to target state Medicaid payments as an area to slow down growing costs.

Uninsured Patients

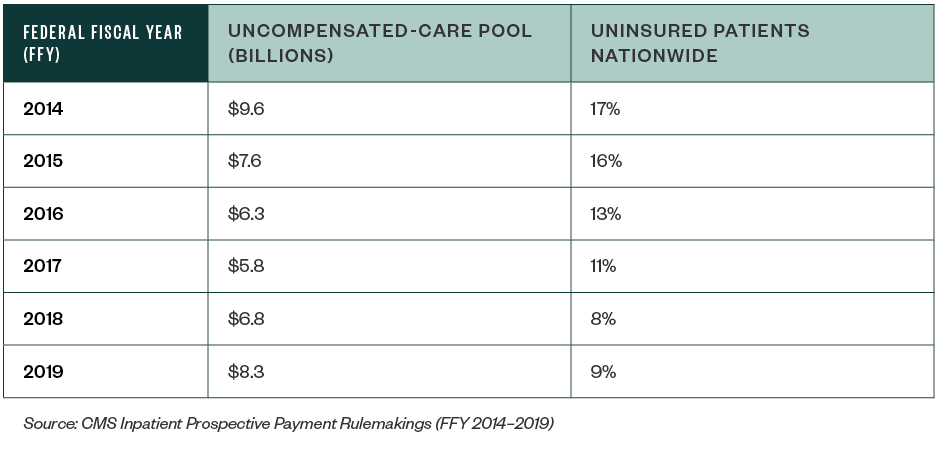

Under the ACA, the federal government uses the number of uninsured patients—which has steadily declined since 2014—to determine the amount that needs to be diverted from the uncompensated-care pool to other programs under the ACA.

The table below illustrates the direct relationship between the uncompensated-care pool available for distribution and the percentage of uninsured patients nationwide as measured by the CBO.

Relationship between Uncompensated-Care Pool and Uninsured Patients

In many cases, the change in the uninsured rate was related to high-deductible health plans and Medicaid-plan expansion. This meant that although more patients were insured, hospitals were being reimbursed at lower rates compared to the cost of patient care—or receiving no payment at all in the case of charity care and other bad debt.

Disproportionate-Share Hospitals (DSHs)

DSHs serve a disproportionate number of low-income and uninsured patients, receiving payments from CMS to help cover some of these costs. Under the ACA, the calculation of these payments has changed to account for the expansion of Medicaid on a state-by-state basis and coverage on the exchanges nationwide.

Previously, Medicare handled DSH payments as an add-on to the payment for inpatient services using a threshold calculation of the hospital’s Supplemental Security Income (SSI) ratio and the percentage of Medicaid days to total patient days.

Under the ACA, the algorithm was modified to take the previous pool of DSH funds and redistribute them in the following manner:

- 25%—referred to as the empirical DSH payment—is still handled as an add-on to each claim using the prior methodology and settled on the hospital’s annual Medicare cost report.

- 75%—referred to as the uncompensated care pool— is distributed to the same population of hospitals based on factors that account for the change in the uninsured population nationwide as well as hospital-specific data.

Medicaid Expansion

Compounding this issue is the fact that several states opted not to expand their Medicaid program. Due to this policy decision, these states continue to see an increasing number of uninsured patients in their communities. For example, the rate of uninsured patients in Texas was nearly 19.5% in 2017—far above the 11% uninsured rate nationwide—and certain areas of the state have even higher uninsured rates.

States with the Highest Uninsured Patient Rates

- Texas

- Oklahoma

- Alaska (recently expanded its Medicaid coverage)

- Georgia

- Mississippi

In the first few years of the new uncompensated-care-pool distribution, hospitals in expansion states realized a small benefit from increased Medicaid plan reimbursements because of a swell in patients who were previously uninsured but became eligible for Medicaid. This resulted in an increase in Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) reimbursements as the ratio of their Medicaid patients grew as a percentage of their total patient population.

Hospitals in the nonexpansion states listed above didn’t realize the same benefit, however, because it depended on an expanded Medicaid population.

Charity Care and Bad Debt

In addition to the changes in the level of insured patients, certain providers are also beginning the process to overhaul the reporting of patient charges, charity care, and bad-debt expense to meet the new revenue recognition standards issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

Charity care and community benefits are two areas that affect not-for-profit hospitals in many ways. From reporting on the IRS Form 990 to the Medicare cost report and audited financial statements, the outcome of serving uninsured and underinsured patients impacts a hospital’s:

- Tax-exempt status

- Level of reimbursement from government payers

- Overall bottom line

Medicare Cost Report Worksheet S-10

In federal fiscal years 2013 through 2017, the distribution of the uncompensated-care pool to eligible hospitals was driven by a calculation of the hospital’s Medicaid days and SSI days compared to the national average.

This calculation wasn’t dramatically different from the historical settlement calculation of DSH dollars on each hospital’s annual Medicare cost report, but it allowed CMS to account for the reduction in the number of uninsured patients in the overall amount paid before distributing the remainder.

Beginning in federal fiscal year 2018, CMS added a third element to the hospital-specific calculation: calculated uncompensated-care cost from each eligible hospital’s Worksheet S-10. It’s important to note CMS is only using the uncompensated-care cost amount, which doesn’t include the shortfall from Medicaid programs—another section of Worksheet S-10.

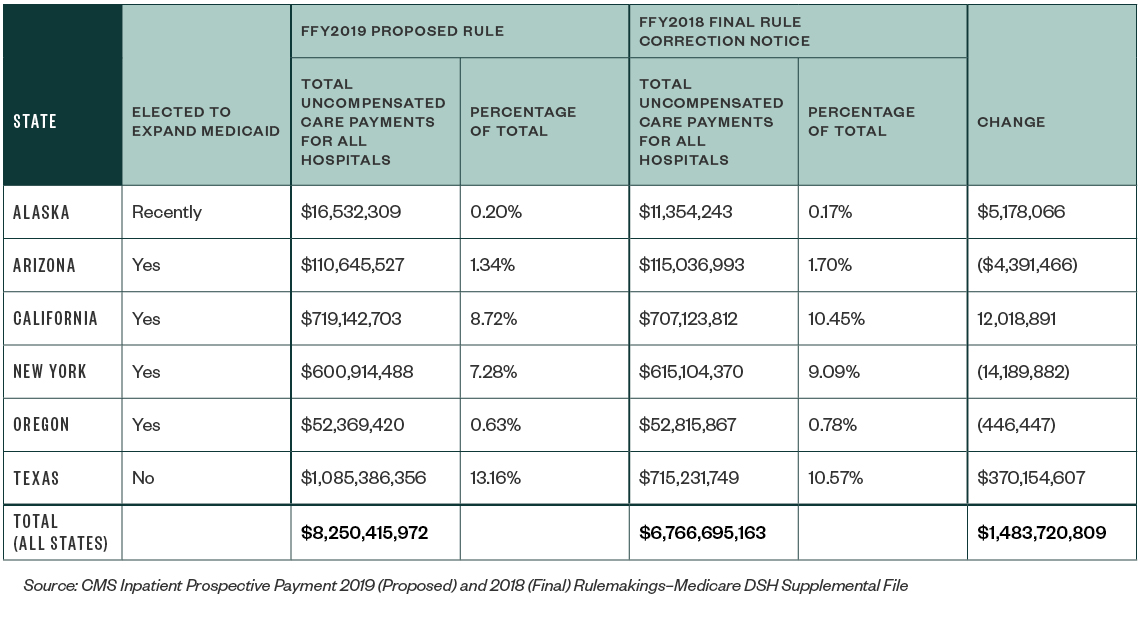

This creates issues for hospitals in states that expanded their Medicaid program. While expansion decreases their uninsured populations, the amount of reimbursement they receive from Medicaid plans falls far short of the cost of patient care. And with the new calculation, more money will be diverted from the uncompensated-care pool to hospitals with high charity-care costs due to uninsured patient populations.

Many groups, including the American Hospital Association, American Federation of Hospitals, and Healthcare Financial Management Association, have provided CMS with written comments and concerns about the use of Worksheet S-10 data in calculating reimbursement for inpatient services. These concerns include the following:

- Unclear nature of the worksheet’s instructions

- Inconsistent nature in which hospitals apply their charity care policies nationwide, either due to organization type or varying demands of government bodies

- Worksheet data that hasn’t been audited by Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs)

Commenters have emphasized that it’s especially unusual for CMS to overhaul payment methodologies using data that hasn’t been reviewed by a MAC or assessed by CMS for aberrations that may create issues down the line for hospitals.

Uncompensated-Care Reimbursement in Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2019

Texas—a state that didn’t expand its Medicaid program—has been the largest beneficiary of this change, gaining a significant increase in its inpatient reimbursement. Hospitals in New York and other states, on the other hand, will see declining reimbursement rates due to their Medicaid expansion and other factors.

Looking Forward

Three factors will serve to increase the level of Americans without insurance:

- Elimination of the individual mandate penalty

- Increase in national debt and GDP spending

- Reduction in Medicaid spending

For individuals able to pay rising premium costs due to the increase in uninsured individuals, the current trend of high-deductible plans is expected to grow.

Under these plans, the monthly premiums grow at a slower rate in exchange for policies that require higher deductibles from the consumer if they use their coverage for services beyond certain preventive care issues. These high deductibles are often more than families can afford to pay, however, which means a family member being unexpectedly hospitalized will often lead to bad-debt write-offs for providers that are unable to collect the deductibles from patients.

This creates a system of underinsured individuals who technically have insurance, but who often can’t use it without being billed beyond what they can afford to pay.

With these factors weighing on hospitals financial assistance programs and the ability to meet patient’s unmet needs, it will be vital for hospitals nationwide to capture and report the most accurate information available to optimize their reimbursement and sustain operations. As Medicare and Medicaid begin to evolve payment mechanisms that more closely align with each hospitals quality of care, service to indigent patients and ability to bend cost curves, understanding the full picture of their marketplace and patient demographics will correlate to better outcomes.

We’re Here to Help

To learn more about the effects of tax reform and Medicaid expansion—and implications for your organization, contact your Moss Adams professional.