This article is part one of a three-part series on the cost of goods sold—a key metric that can help wineries understand their profit margins. In this article we provide an overview of how to calculate the cost of goods sold (COGS) and why it matters. In the second article we dive into steps for setting up a system and best practices to derive this metric, and in the final article we discuss specific COGS insights for wineries by case volume.

To evaluate your winery’s performance, it’s essential to have insight into its profit margins. Your winery’s profitability is driven by two things–what you can charge for your wine and what it costs to make and sell it.

The market generally determines what someone is willing to pay for your wine, so the cost of making and selling that wine largely determines how much profit is left over. The greater understanding and control you have over your costs, the greater your chance for running a profitable winery. This is why knowing what it costs to make your wine is so important.

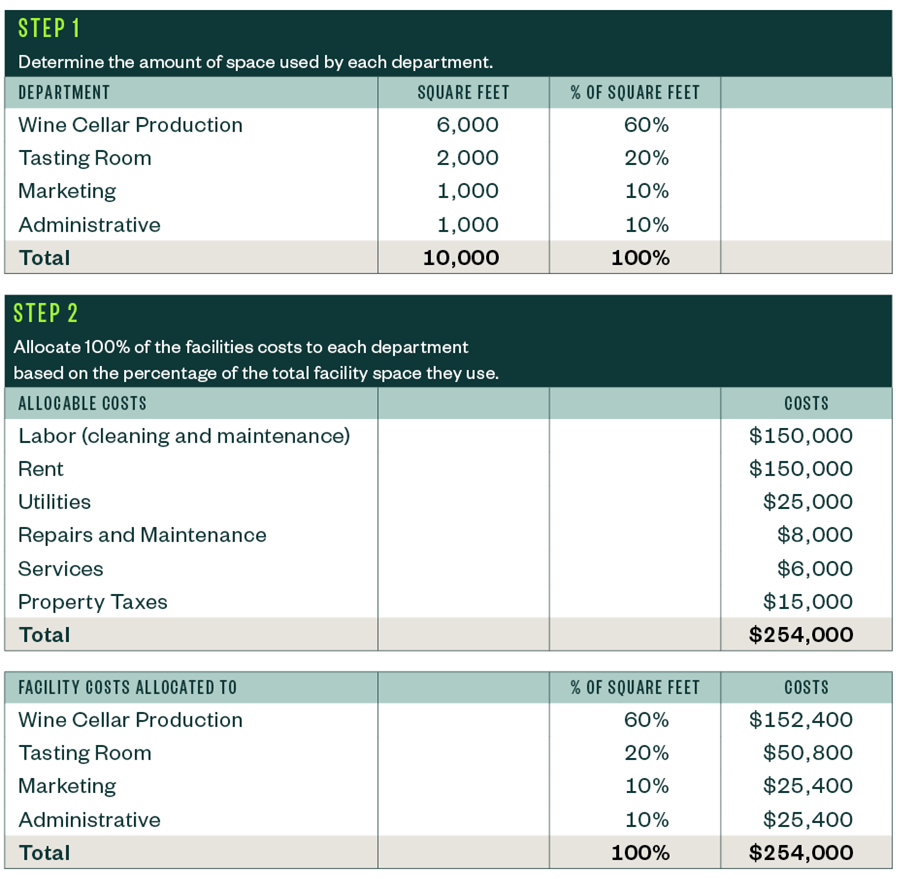

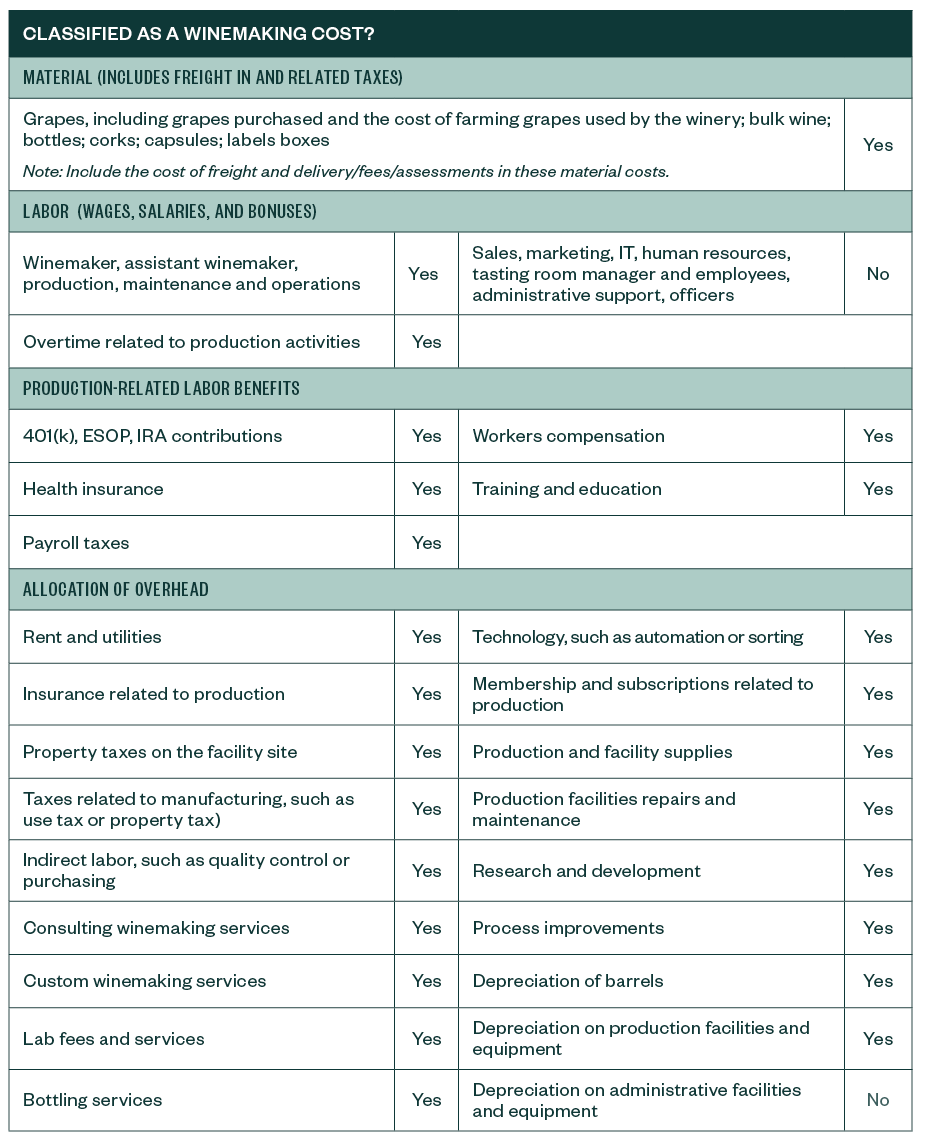

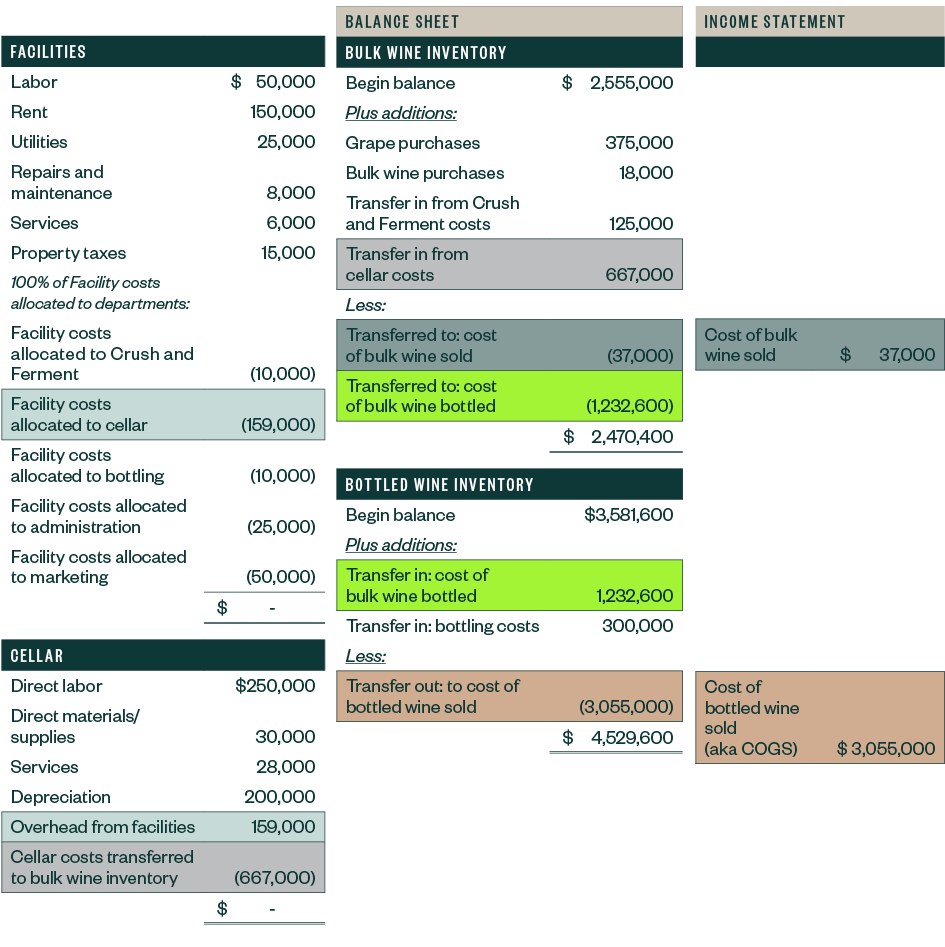

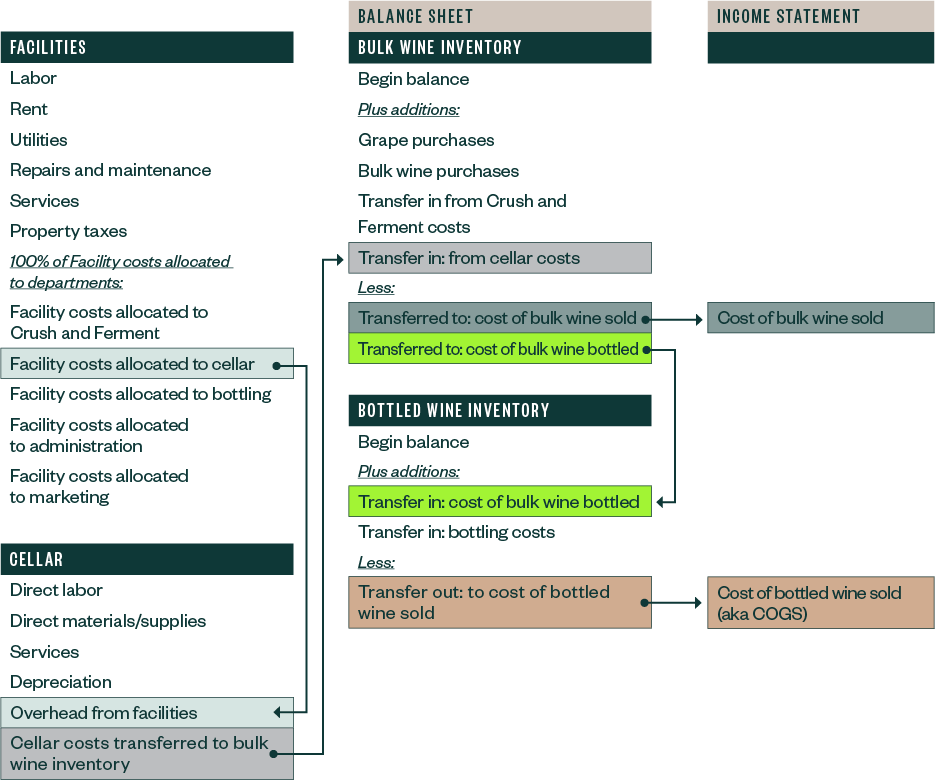

While this might sound simple, there are many challenges associated with calculating the final cost of your wine. This includes determining what expenditures to include in production costs and how to allocate them as well as accurately tracking the costs and movement of your wine inventory throughout the winemaking process by varietal as well as by vintage and blend.

In this article, we’ll break down how to obtain the information you need to understand your profits and costs—including relevant accounting basics and strategies to categorize various production costs.

Accounting: The Basics

In order to know your cost of goods sold (COGS) in a period you must first know what it cost you to produce those wines—this is referred to as the Cost of Goods Produced (COGP).

Here’s how they’re defined in the context of wineries:

- COGP. Also known as wine in process (WIP), this encompasses all costs involved in the process of making wine. It includes the raw materials, services, labor and overhead—direct and indirect costs—costs incurred up to, and through the point of bottling the finished wine.

- COGS. This is the cost—COGP—previously incurred in making the specific wines that were subsequently sold during a given period, such as a month, quarter, or year. It’s important to note that, as the name implies, COGS only refers to the cost of wines sold during a given period—not the costs incurred in the process of making wine during that period.

Consistent with best practices, when a wine is sold, the cost of having made that specific wine is recorded as COGS, concurrently with recording the revenue from the sale of that wine. There can be other items that impact COGS specific to the accounting method used as well as other specific business cases that can be discussed further with your CPA. The difference between the revenue generated and the wine’s COGS is ultimately the gross profit on that wine.

Understanding Gross Profit Margins

One of the first measures of gauging a winery’s profitability is its gross profit margin. You can calculate a winery’s gross profit margin in two steps:

Accounting Methodology

When calculating the cost of making and selling wine, it’s typically recommended to use accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America (U.S. GAAP). Usually, U.S. GAAP is the standard used for financial statements in business. From a management perspective, U.S. GAAP basis accounting is typically considered a more accurate reflection of a business’s performance rather than tax basis accounting or another financial reporting framework.

Inventory Methods

The elongated, often multi-year production process for making wine presents specific challenges in inventory costing because there can be significant time lag—often several years—between when the production costs are incurred and when the wine is sold and the associated production costs are recognized in the income statement as COGS. The long production process means wineries usually have multiple years or vintages of wine on hand in different stages of production.

For this reason, most wineries track and report their wine inventory costs in separate inventory pools such as bulk wine, packaging materials, and finished cased wine.