As the popularity of online travel companies (OTCs) such as Expedia, Travelocity, and Orbitz continues to increase, many municipalities are rewriting or clarifying transient occupancy tax regulations for short-term rentals.

As the popularity of online travel companies (OTCs) such as Expedia, Travelocity, and Orbitz continues to increase, many municipalities are rewriting or clarifying transient occupancy tax regulations for short-term rentals.

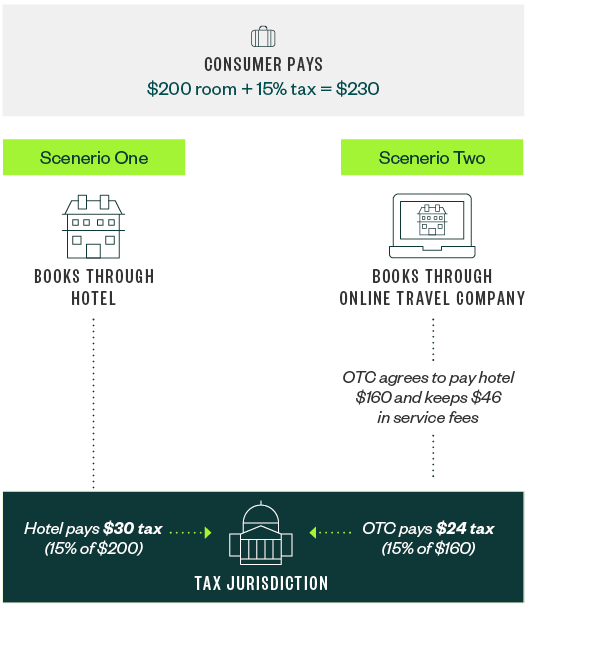

This clarification responds to legislation loopholes and ambiguities in the ways OTCs remit taxes. Because the methods OTCs use to deliver services can complicate tax remission, OTCs can end up remitting fewer taxes than hotels, despite charging the same amount—or more—for a hotel room. As a result, states and communities are losing out on revenue needed to support their infrastructures, and OTCs are failing to remain compliant with state, county, or city laws.

Background

Transient occupancy tax is levied on the cost for operators to provide accommodations. It varies greatly by state, county, and city. Before hotel and motel operators began listing room availability on online platforms, paying the transient occupancy tax was relatively straightforward: A transaction occurred between the operator and the client and, according to many municipalities, the operator payed the tax from a percentage of the rental’s retail rate.

This relationship became more ambiguous, however, with the introduction of third-party OTCs. In many cases, unclear or out-of-date legislation resulted in tax remission ambiguities that allowed OTCs to classify themselves as service providers, while taxing jurisdictions viewed them as operators with corresponding rental charges. This difference in categorization led to municipalities claiming OTCs were paying too little in transient occupancy taxes.

In response to this issue, the National Conference of State Legislatures and other legislative bodies have recommended municipalities clarify their laws to ensure OTCs are paying the full and correct amount in transient occupancy taxes.

The Requirements

In the United States, there are thousands of different occupancy taxes imposed at various jurisdictional levels—including state, county, city, and even special tourism areas. Each location has its own ordinances, and multiple levels of occupancy taxes can apply to a single transaction—meaning companies must consider and abide by each of them.

To add to the complexity, OTCs are subject to the taxes imposed by the municipality in the district where the property is located—not by the laws that apply to the location where a company is based. This means a company must understand and remain compliant with laws that apply to each location where they do business.

Example

The city of Houston is located in Harris county, and both jurisdictions have separate laws with which providers need to comply. To further complicate the picture, the 17% hotel tax in Houston isn’t just the combination of city and county transient occupancy tax laws—it’s the combination of a 6% state tax, 7% county tax, 2% city tax, and 2% tax by the body that oversees the city’s tourism and sports venues.

If an OTC that’s based in Florida provides a short-term rental in Houston, it’s subject to Houston’s 17% transient occupancy tax. The OTC must understand the nuances of all these various taxing jurisdictions, regardless of how frequently the OTC offers rooms in the locality. If the company fails to comply, it could be subject to substantial penalties.

Legislation Ambiguities

There are currently thousands of jurisdictions in the United Sates that affect transient occupancy taxes, and the legislation ambiguity has led to many lawsuits with each case reaching a different conclusion. Here are two of the major inconsistencies within the legislation that make collecting and remitting the tax—and determining who’s responsible for doing so—challenging for OTCs.

Defining the Operator

While many municipalities state the operator is responsible for paying the tax, laws often fail to define what constitutes an operator, rentor, or lessor—the hotel that places the listing, the online platform advertising the listing, or, in the case of personal dwellings, the owner of the property.

In an attempt to address this issue, jurisdictions are currently updating their laws to read differently. Whereas former language stated the operator was responsible for the tax, many laws now overtly include OTCs in their definition of an operator.

Example

The Colorado Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari to the Town of Breckenridge to determine if OTCs are responsible for occupancy taxes. The case is against 16 different OTCs, and the District Court as well as the Colorado Court of Appeals determined the OTCs weren’t renters or lessors. Oral arguments were heard on March 2, 2019, but a decision hasn’t been issued.

As this approach continues to prove effective, many jurisdictions, specifically neighboring cities, are expected to continue following each other’s proven methods for acquiring transient occupancy tax money.

Determining the Taxable Rate

Legislation in many districts doesn’t specify which amount of the short-term rental cost should be taxed—the price the OTC charges their customers (retail rate), or the smaller amount they pay to the hotel they’re advertising (wholesale rate). Many OTCs argue that part of the price paid by customers is the OTC service fee and the transient occupancy tax shouldn’t apply to that percentage of the fee.

However, this argument has proven incorrect in many instances. This is because hotels and motels provide similar services at similar rates, despite being a different channel of distribution.

Example

Here’s a look at how rental costs and the transient occupancy tax are broken down for hotels and OTCs.

OTC Responses

While many large OTCs have the resources to voluntarily collect and remit transient occupancy tax for property owners—and do so to gain a competitive advantage—many smaller platforms can’t afford to pay the tax or don’t have the administrative resources to do so.

In these instances, smaller OTCs often include contract language stating that property owners or customers are responsible for the tax. However, there are two problems with this approach:

- Customers and property owners often don’t end up paying the tax. This is because customers don’t know they’re responsible for the tax and property owners aren’t involved in the exchange of money—meaning they don’t have a method to remit taxes. This means the state or municipality doesn’t get paid.

- OTCs aren’t legally allowed determine who pays the tax. It’s determined by state, county, and city municipalities.

Many OTCs may not be complying with transient occupancy tax laws despite their precautions. In these instances, jurisdictions are contacting companies, requesting they voluntarily register to collect and remit the tax, or retroactively collecting the correct amounts directly from the company.

We’re Here to Help

Transient occupancy tax laws are expected to continue changing as jurisdictions clarify their requirements. To learn more about how this legislation could affect your or your business, contact your Moss Adams professional.